Zootopia: 7 facts about the zoos – the good, the bad, and the ugly

Are zoos good or bad is among the many polarizing questions these days.

When I was a little girl my grandma took me to the zoo. My most vivid memory of that trip is seeing a polar bear sitting on some ice, but mostly surrounded by lush greenery, looking lethargic and miserable, and me thinking ‘that bear does not belong here’.

My encounter did not push me to become a biologist, or a vet, or engage in any other scientific matter — which is what some proponents of zoos claim to be their influence on children. Instead, it inspired me to become an ‘explorer’ (my 6-year-old mind fixed on Dora and convinced it was a legit profession), and to one day see the polar bears in their natural environment.

Back in the day, a weekend trip to a zoo or an evening at the circus was standard family time out.

It’s delusional to think that it is our right to see exotic wildlife like gorillas, dolphins, and elephants in every major city.

Luckily, we’ve mostly moved on from circus animal acts since, transitioning to performances of entirely human circus troops, such as the famed awe-inspiring Canadian Cirque de Soleil.

But zoos have stuck around.

It’s true that today zoos don’t just cater to the recreational needs of visitors, but also contributing to research and conservation of animals. However, the way wildlife is inevitably being forced to live in unnatural conditions still raises concerns about their wellbeing in the confines of the zoological gardens.

With zoo authorities claiming to be imperative in saving endangered animal species on one side, and animal rights organizations vocal on the issue of animal abuse on the other; it’s more important than ever to educate ourselves on what goes on in the enclosures, try to understand how zoos actually function, and make an informed decision about which — if any — zoo to support.

Here are some facts to consider before your next visit:

1. A brief history

The concept of zoo is nothing new — captive animals have been entertaining ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians. A zoo discovered in Egypt in 2009 and was believed to have existed in 3,500 BC. Evidence of elephants, wildcats and hippopotamus was discovered at the location.

Later, in medieval England, Henry III moved his private royal menagerie to the Tower of London for public viewing. For a fee, Londoners would be treated to glimpses of animals like lions, camels and lynxes. And if they brought a dog or cat to feed the lions, their entrance fee would be waived.

The way wildlife is inevitably being forced to live in unnatural conditions still raises concerns about their well-being.

The first zoological garden as we know it today, the Imperial Menagerie in Vienna, Austria, was established in 1752 and continues to attract visitors to this day. In 1793, in Paris the menageries of French aristrocrats were taken by leaders of the French Revolution and relocated to the Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes. Animals were kept in small display areas, with as many species as space would allow.

Berlin Zoo followed in 1844. It is home to the world’s largest wildlife collection of nearly 20,000 animals from over 1,400 species and has set modern day zoo standards.

2. Just like home — or is it?

The modern zoos are very aware of the conditions needed to mirror the natural habitat as closely as possible and maintain proper health and behavior of the animals.

Activities are arranged to help keep them mentally alert and physically active, which to some extent eliminates the boredom, deterioration, and eventual degradation of the animal at the zoo.

Some habitats a zoo simply cannot replicate.

However, none of it replaces hunting, migration, and other natural patterns. Locking wild animals up deprives them of the much-needed freedom. This is worst for animals that need to migrate and/or move around a lot.

Clearly, that was the case for my polar bear — a polar bear’s natural range may be about a million times the size of a zoo enclosure! Lowland gorillas in the wild have a range of up to 16 miles.

Wild animals are connected to their natural surroundings and this bond is broken when they are put into artificial settings of a zoo.

So while some species, such as lemurs, can thrive in captivity, the likes of elephants have the need to travel long distances, and in large groups. Confining them into small spaces deprives them of their migratory nature. A herd of 40+ elephants is known to travel between 30–50 kilometers every day!

Similarly, predatory animals, such as lions, will not get the chance to hunt, making them more aggressive if they are not properly taken care of.

That is a habitat which a zoo simply cannot replicate. Wild animals are connected to their natural surroundings and this bond is broken when they are put into artificial settings of a zoo.

If and when they are eventually released in the wild, they find it difficult to adapt to the new environment, which is far different from the zoos. And for those born in the zoo, it would be like a double-edged sword — being released into the wild risk their survival as they lack the natural capabilities to hunt for themselves.

3. Survival of the fittest

Captive breeding programs are implemented to help preserve animals that have decreased in number, which is a good way to prevent extinction of some species. In fact, as is the case for some species, zoo populations may be all we have left.

Zoos around the world work together to preserve them. These connections make it possible to bring a pair of animals together to begin the mating process so that the species can continue living. If these rare animals were forced to find each other in the wild, the result could be very different.

In case of some species, zoo populations may be all we have left.

San Diego Zoo Global helped pioneer artificial insemination for pandas, and this science has been a cornerstone of saving the species. They continue to work closely with partners on breeding and reintroduction programs today. In addition, they support protected reserves in China where pandas can live safely and thrive in their natural environment.

Other past success stories include the regeneration of Arabian Oryx, Golden Lion Tamarin, Puerto Rican Parrot, Californian Condor and the Przewalski Horse.

Unfortunately, this is sometimes a marketing gimmick rather than an true mission. And while some establishments are genuinely trying to do their best to let animals mate, it is quite common to have the new offspring kept at the same zoo, be moved to another one, or sold to raise money, which essentially does nothing for the numbers of the species in the wild.

4. Learning. The hard way.

Large exotic animals secured in enclosures is what allows scientists to perform studies and research.

Some modern zoos work with colleges and universities to create thorough degree programs. The zoos have training and residency programs for veterinary and zoology students so they can train first hand and become world-class zoological medicine specialists.

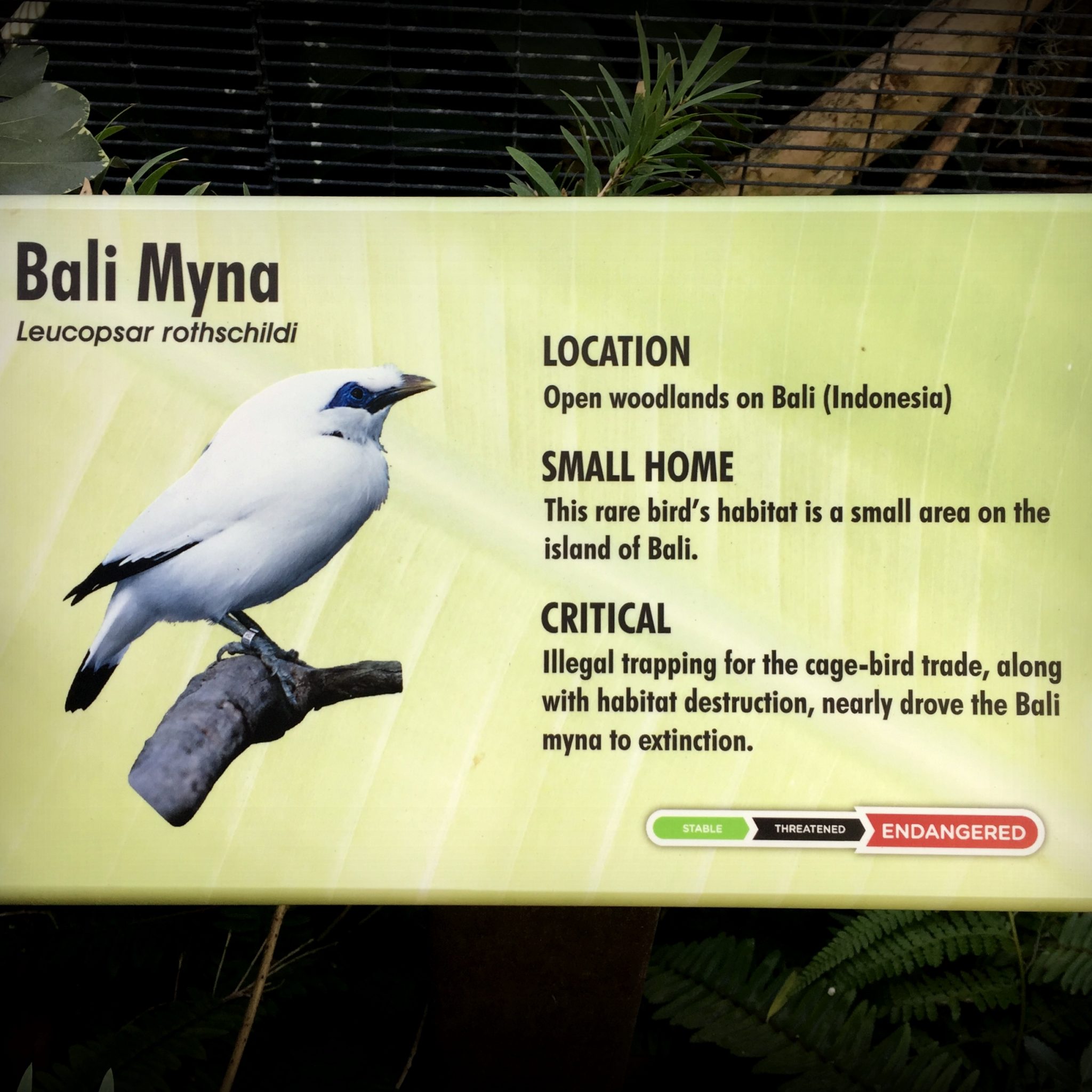

For the general public, these days zoo authorities place a greater emphasis on engaging and educating visitors rather serving as merely a recreational venue. Many school children visit zoos to learn more about endangered species and how to conserve them via interactive displays.

The signboards in zoos provide useful details about animals including their scientific name, habitat, origin, diet, etc. We can can easily dive into the animal world without having to travel to far off places.

But then again, for most zoo visitors it’s little more than a fun day out. Most go to look at the animals and nothing more, and children learn early on an animal in captivity can be entertainment.

And if the animals do not exhibit their natural behavioral traits in zoos, is studying a zoo animal going to reveal much about its natural instincts?

5. By the people, for the people

Yes, the conservation and education aspects do matter, but statistically no more than a fifth of the animals in any given zoo belong to rare or endangered species.

Zoos are, first and foremost, for our entertainment and have always existed primarily to serve the human gaze. This isn’t just an ethical problem. Most animals simply don’t want to be stared at — it causes a huge deal of distress.

If the animals do not exhibit their natural behavioral traits in zoos, is studying a zoo animal going to reveal much about its natural instincts?

The fact that animals are placed in captivity for the purpose of human entertainment, has been subject to an ongoing philosophical debate, and is one of the main reasons of the existing anti-zoo campaigns.

The other side of the coin is that for many of us around the world, zoos represent an (only) opportunity to experience seeing species that would be impossible to do otherwise.

You might also like: TURTLES VS TOURISTS: HOW MASS TOURISM AFFECTS OSTIONAL WILDLIFE RESERVE, TOP TED TALKS FOR THE RESPONSIBLE TRAVELER

6. Zoochosis is real

No matter how good the facilities in zoos are, animals tend to suffer in the confines and constantly live in psychological pressure, which tends to reflect in their abnormal behavior. Animals born in a captive environment most likely never get to see the world outside the confines.

Locked up for an indefinite period of time, these animals don’t know how to cope with their newfound stress, anxiety, and constraints. And rightly so — being in enclosed spaces that can only attempt to recreate a natural wild habitat is like putting a human in a super sized doll house for the rest of his life.

Animals born in a captive environment most likely never get to see the world outside the confines.

Unsurprisingly, scientists started to observe the psychological impact that this sort of confinement is having on zoo animals and the results aren’t good. The term “zoochosis” was coined in 1992 by Bill Travers to characterize the obsessive, repetitive behaviors exhibited by animals kept in captivity.

The short documentary “Zoochosis” digs into the underlying causes of these abnormal, seemingly mindless behaviors.

7. Safe haven?

Zoo animals receive proper nutrition and medical care and are supervised by well trained zookeepers and in most cases extremely caring staff who are willing to help them in the event of emergencies.

They receive regular screenings, quarantine procedures, parasite removal etc. Treatment teams at most zoos include veterinarians, pathologists, technicians and other specialists who can create and maintain virtually any care plan for the creature in need.

Life in a zoo is a zero sum game.

(Fortunately, because it turns out animals in captivity require a lot of treatment. Psycho-pharmaceuticals related to the aforementioned zoochosis are in high demand, the animal pharmaceutical industry is booming, and the subject is largely taboo.)

Finally, with the rise in poaching of wild animals for fur, ivory and other parts with supposed medicinal benefits, zoos appear to be a safe space for those in-demand species. Although poachers have been able to break into zoos to take animals in the past, this is not a frequent occurrence and is normally not successful when it does occur.

The question is, is this a long term solution to the poaching problem? Zoos can protect the individual, say, rhino, but in exchange for protection the rhino loses its habitat.

Life in a zoo is thus a zero sum game and is far from an antidote for education, raising awareness and changing the mindset of those who create demand for its horns.

Our desire to interact with animals is a good impulse. But if not zoos, then what?

Laurel Braitman, author of Animal Madness, offered a prescription while talking to Slate: “End zoos as we know them and replace them with hands-on petting zoos, teaching farms, and wildlife rehabilitation centers, where people can interact with the kinds of animals who often thrive in our presence, such as horses, donkeys, llamas, cows, pigs, goats, rabbits”.

She highlights that it’s delusional to think that “it is our right to see exotic wildlife like gorillas, dolphins, and elephants in every major city … especially since it often costs the animals their sanity.”

I have yet to see a polar bears in the wild, in case you’re wondering.

And I better hurry. Since my encounter with the sad looking bear, their population in the wild decreased significantly, largely due to human-induced climate change and melting glaciers, oil and gas extraction and marine pollution.

I remain skeptical about the very nature of the zoo. Wildlife, after all, belongs in the wild.

Several zoos have greatly contributed to the survival of the species. Without their ongoing research and conservation efforts there may not be any polar bears left by the time I finally make it to the Arctic Circle.

But I remain skeptical about the very nature of the zoo. Wildlife, afterall, belongs in the wild.

Do you think zoos are ethical? What are your thoughts on the subject? Let us know in the comments below!

Images: Gaby Aziz Featured Image: Omar Ram for Unsplash